Kilneuair Chapel

Writing in ‘The Kist’ in 1994, the historian Lady McGrigor said:

“The old church of Kilneuair (Cill an Iubhair, Chapel of the Yews), once important in the district as the parish church of Glassary, is now quite difficult to find.”

She wasn’t kidding. Twenty-six years later, with forest plantations growing up all around it, it’s even harder to find, and the task isn’t made any easier if you start off on the wrong track and end up following deer paths (that’s what I was assured they were) through stands of conifers so densely planted that you have to push through them backwards in order to protect your eyes.

Added to which, I’d chosen to wear wellies but the thick frost proved extremely slippery on near-vertical slopes. A lot of clambering took place, and some mildly colourful expressions of surprise at the gradient.

We made it, though, largely because Colin can find his way out of any woodland, and also because the idea of giving up and retracing our steps wasn’t all that appealing. And there were advantages to taking the ‘scenic’ route: through gaps in the trees we had fine views down Loch Awe, which was draped in mist and partially frozen; and three woodcock burst up out of cover, much to Colin’s delight.

Ruins just visible, middle distance

The final hurdle was a field of dead bracken, stiff spiky lances that reached well above head height, but by then the chapel could be seen with its lovely stones gleaming on the opposite slope. We emerged triumphant and dishevelled, and just stood and gazed at it. It was beautiful.

What on earth is a chapel doing here, on a craggy and uninhabited hillside above Loch Awe? Not just any chapel, either: according to some historians, this may be the site of a ‘lost’ chapel established by St Columba:

“Campbell and Sandeman (1964) translates ‘Kilneuair’ as ‘Coille-nan-Iubhair’, i.e. ‘Yew Wood’ and suggests that this may be the Columbian site ‘Cella Diuni’ mentioned by Adomnan [St Columba’s biographer] which was certainly in the Loch Awe area and has not hitherto been identified.” (Canmore)

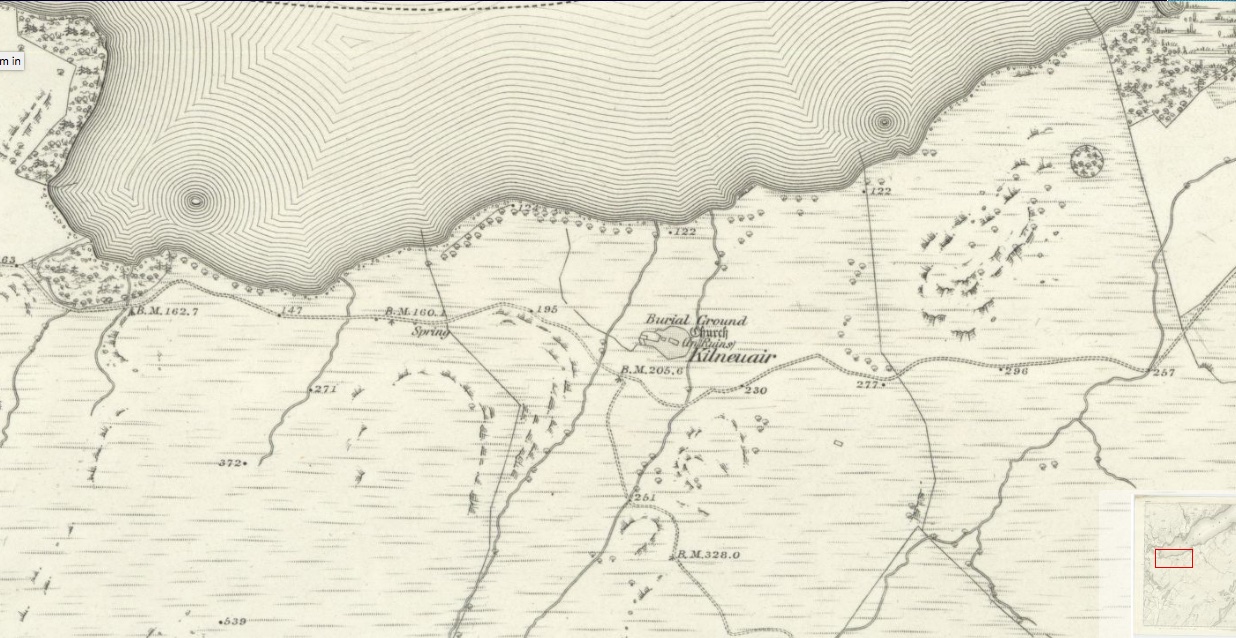

Nor, it appears, was Kilneuair (approximately pronounced as ‘Kill-nure’) always so isolated. There are traces of a settlement nearby, which was also called Kilneuair, and the six-inch OS map of 1875 shows the road down Loch Awe passing very close to the chapel, before branching off to the south-east on a winding trail that eventually comes out on the shore of Loch Fyne. There is even an old story that stones for building the chapel were passed from hand to hand by a human chain stretching from a quarry at Killevin near Crarae on Loch Fyne; an alternative version claims that Killevin chapel itself, which no longer stands in its old graveyard, was dismantled block by block and re-built at Kilneuair.

6″ OS map of 1875, showing Kilneuair and the old tracks (National Library of Scotland)

6″ OS map of 1875, showing Kilneuair and the old tracks (National Library of Scotland)

Whatever the truth of the matter, in former centuries this little spot would have been very familiar to wayfarers. The surveyor’s report of 1970, quoted in Canmore, states that “a village once lay round the church, and a market, called A’ Margadh Dubh – ‘the Black Market’ – perhaps in contrast to the gaiety of Kilmichael Tryst – was held here.” Kilmichael Tryst was a popular market for cattle drovers, but according to Lady McGrigor, the one held at Kilneuair was very similar. She says: “…the great cattle market held annually at its gates must have been an important event.” I wonder whether it was called ‘black’ from the colour of the cattle.

Our first task, once we had dusted ourselves off, was to look properly at the ruins and make some kind of sense of them. The chapel survives as a long rectangular building, now roofless, its crumbling stonework colonised by trees and ivy. Over time, the walls have been propped up in places by timber joists and buttresses and even a few courses of brick. I’d read that it is longer than most early Christian chapels, and on close inspection it was fairly easy to make out the oldest part, which lies to the east. Even this, however, is not thought to date from St Columba’s time (the sixth century) but instead from the late 13th century; this progression seems to be quite common in other similar chapels here in Argyll, where the original structure has been replaced by (or incorporated into) a medieval chapel. Canmore explains:

Our first task, once we had dusted ourselves off, was to look properly at the ruins and make some kind of sense of them. The chapel survives as a long rectangular building, now roofless, its crumbling stonework colonised by trees and ivy. Over time, the walls have been propped up in places by timber joists and buttresses and even a few courses of brick. I’d read that it is longer than most early Christian chapels, and on close inspection it was fairly easy to make out the oldest part, which lies to the east. Even this, however, is not thought to date from St Columba’s time (the sixth century) but instead from the late 13th century; this progression seems to be quite common in other similar chapels here in Argyll, where the original structure has been replaced by (or incorporated into) a medieval chapel. Canmore explains:

“The name ‘Kilneuair’ which is applied to the site (Kilnewir, 1394; Killenevir, 1490; Killenure, 1671) suggests an earlier church, and an older, roughly circular enclosure can be traced inside the churchyard wall, especially on the west and north.”

The west end

The south wall, seen across the crumbling remains of the north wall

The south wall, seen across the crumbling remains of the north wall

Supporting buttresses becoming a kind of relic in their own right

Looking down the chancel and nave from the east end

At the old east end, near where the altar would have stood, is an aumbry or recess where precious artefacts would have been kept; and next to it a stone carved with a trefoil design is described as a “damaged piscina of epidiorite.” A piscina would have contained a basin of water for priests to wash their hands or rinse items such as goblets. I can only imagine that this stone therefore is a fragment of a once-larger feature, such as a bowl that projected from the wall. Epidiorite is a particularly hard type of stone, often favoured by stonemasons because it retains its detail in the face of relentless weathering.

Aumbry and piscina

The western half of the chapel is thought to be later in date: the south wall of this section may have been built in the 16th century, while the north wall may be slightly earlier. Much of the north wall has long since collapsed. The exact reason for extending the building is obscure, but it may just have been for the simple purpose of accommodating a larger congregation. Until the 16th century this was the principal church in Glassary, a large parish which stretched from the south-east of Loch Awe down to the north-west shore of Loch Fyne. Its dedication to Iona’s saint is remembered in its local name, ‘the church of St Columba in Glassary’. By the early 17th century, however, it must have fallen out of use, and its role was taken over by a church at Kilmichael.

One of the most recognisable features to survive is a medieval font, which stands in the western half of the church. Again, it is carved from epidiorite, but much of the original surface lies hidden beneath moss and lichen. The notch in the rim is thought to be a later addition, possibly for domestic use. It sits on what is considered to be its original plinth, the entire structure placed atop an old millstone – now, like so many other features, concealed by moss.

The font at the western end, and the doorway through which a spooked tailor is supposed to have escaped

Much more elusive are the Devil’s claw-marks, which, according to tradition, are said to be scored into a stone on the eastern side of the doorway into the nave. I don’t know why it should be disappointing when you can’t find something that is ascribed to the Devil! I did look very hard at both doorways, but couldn’t see anything that looked remotely suspicious. This is the story of how they came about: the church was once believed to be haunted, and a local tailor accepted a bet that he couldn’t stay there all night on his own. Full of confidence, he settled down in the nave, and became absorbed in his stitching. However, towards midnight a huge hand materialised out of the ground in front of him, followed by the rest of a dark, giant figure. Horrified, the tailor made a dash for the door and got outside just in time; the Devil’s claws, snatching at him in vain, lacerated the stone wall instead.

This tale bears an uncanny resemblance to another story, relating to Saddell Abbey in Kintyre. The ruins there are said to be haunted by a huge spectral hand, which once pursued a man – again, a tailor – from the Abbey to Saddell Castle, a few hundred yards away. The tailor just managed to get inside the castle safely, but the Devil’s handprint is still said to be preserved on the left-hand side of the door. Apart from anything else, why were tailors singled out? Was there a symbolic significance? Did the Devil want to hijack their handiwork? Or were they just gullible?

The oratory, of uncertain date

A few paces to the west of the chapel stands a smaller, squarish structure with some really fascinating and attractive features: small triangular windows (one now collapsed), not unlike those seen on an old winnowing barn at Arichonan; an arched entrance, now walled up; and some intricate designs carved into alternating stones of the arch and quoins.

This, according to Canmore, is an oratory. Traditionally, an oratory was a private house of prayer, usually small in size, and either attached or adjacent to a larger chapel or church. There seems to be some uncertainty about the age of this one: while Thomas Muir, writing in ‘Characteristics of Old Church Architecture’ (1861) accepts it as an authentic medieval oratory, a surveyor’s report for Canmore in the 1970s describes it as a folly, probably 18th century in date, and comparable with small family burial enclosures in mid-Argyll – although it is interesting to note that no monuments have been identified. Lady McGrigor wonders if it was constructed by the Campbell family of nearby Ederline, but observes that it was already roofless when they sold their property in 1872.

Side (above) and back (below) of oratory

I can’t quite make up my mind about it – not that I’m an expert. The walls are quite thick, and the stonework seems older than 18th century. I wonder if it is an older building that has been given a ‘makeover’ with the addition of embellishments. But equally, why couldn’t the embellished stones have come from the chapel? It’s very interesting. Whatever it originally contained – worshippers, relics, burials – the little oratory is now sheltering some young trees and dense vegetation, and it’s probably a haven for wildlife.

It took us a while to realise that the low green hummocks that were scattered around the south side of the enclosure actually concealed upright gravestones. I was struck afresh by the abundance of moss and lichen: the perimeter wall, for example, was not just partly covered, it was completely enveloped, while the carvings on recumbent grave slabs have been translated into a soft tapestry of moss. One or two of these had familiar knight-effigies on them, like those seen at Kilmory Knap, Kilmartin and elsewhere.

An extraordinary sycamore tree in the boundary wall drew our attention because it had two huge gaping holes in its trunk and was full of water: we gazed into the flooded hollow, which looked like a miniature subterranean cavern. What wonderful natural things you find growing in these places – or are you more tuned in because you’re more aware? Despite the tailor’s unfortunate experience, there’s a gentle sense of peace here. It’s not just about the quiet woodland environment: the abandoned settlements of Kilmory Oib and Arichonan have a very different, unsettling energy.

An extraordinary sycamore tree in the boundary wall drew our attention because it had two huge gaping holes in its trunk and was full of water: we gazed into the flooded hollow, which looked like a miniature subterranean cavern. What wonderful natural things you find growing in these places – or are you more tuned in because you’re more aware? Despite the tailor’s unfortunate experience, there’s a gentle sense of peace here. It’s not just about the quiet woodland environment: the abandoned settlements of Kilmory Oib and Arichonan have a very different, unsettling energy.

The cold was already coming down by mid-afternoon, and the shadows were deepening. We didn’t linger, much as we’d have liked to. We started back down the hill via a less challenging route, leaving the chapel to the burn’s quiet murmurings and the gathering dusk.

An editorial footnote to Lady McGrigor’s article states that, around 1814, a medieval bronze bell-shrine or reliquary with Romanesque decoration was found at Kilmichael Glassary. It contained a much-corroded iron bell of the type used in early Christian chapels. She says: “This may have been the bell belonging to the earliest chapel at Kilneuair… The bell and shrine can be seen in the Royal Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh.” A paper entitled ‘The Kilmichael Glassary Bell-shrine’ (D H Caldwell, S Kirk, G Markus, J Tate, S Webb, Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 2012) examines the reliquary and bell in depth, discusses their possible age and provenance, and describes the historical and legendary uses of saints’ hand-bells. A lovely, and largely intact, cross and chain were found close by and are also linked with the bell.

An editorial footnote to Lady McGrigor’s article states that, around 1814, a medieval bronze bell-shrine or reliquary with Romanesque decoration was found at Kilmichael Glassary. It contained a much-corroded iron bell of the type used in early Christian chapels. She says: “This may have been the bell belonging to the earliest chapel at Kilneuair… The bell and shrine can be seen in the Royal Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh.” A paper entitled ‘The Kilmichael Glassary Bell-shrine’ (D H Caldwell, S Kirk, G Markus, J Tate, S Webb, Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 2012) examines the reliquary and bell in depth, discusses their possible age and provenance, and describes the historical and legendary uses of saints’ hand-bells. A lovely, and largely intact, cross and chain were found close by and are also linked with the bell.

“The bell’s date of manufacture is placed in the 7th-9th century, while the shrine is assigned to the first half of the 12th century. … There is no certainty as to who was the saint associated with the bell. Again, there are aspects of the assemblage itself and the place of its finding which point towards a Columban dedication and a Dunkeld connection but this is by no means certain…”

My grateful thanks to reader Bob Hay for telling me about Kilneuair chapel and sharing memories of his visit in the 1980s.

Reference and further reading:

- Canmore: Kilneuair chapel and oratory (photographs on Canmore’s website show the buildings in former times, and in a slightly better state of preservation.)

- Mary McGrigor, ‘The Old Parish Church of Kilneuair’, The Kist (The Magazine of the Natural History and Antiquarian Society of Mid-Argyll) no.48, 1994

- David H Caldwell, Suzy Kirk, Gilbert Markus, Jim Tate, Sharon Webb, ‘The Kilmichael Glassary Bell-shrine’, Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 142 (2012)

- Thomas Muir, ‘Characteristics of Old Church Architecture &c. in the Mainland and Western Islands of Scotland‘, 1861

- James Murray Mackinlay, ‘Ancient Church Dedications in Scotland‘, 1910-1914

- Map: National Library of Scotland

Images copyright Colin & Jo Woolf

20 Comments

MOIRA GOODMAN

When I read this Jo, I had a picture in my mind of you and Colin battling through the elements to get to where you wanted to be. Just like modern day Explorers!! Very interesting article and the photos are just outstanding. Hope you and all your family have a VERY HAPPY NEW YEAR.

Jo Woolf

Haha, very true – that could be an analogy for our lives, Moira! Glad you enjoyed it and thank you so much for your kind comments. We had fun that day despite the assault course to get there! And the lighting was perfect. We’re all well and hope that you are too, and wishing you all every happiness in the year to come.

Albie Boakes

Really loved this . Thank you for taking me on a journey I can no longer make .

Jo Woolf

You’re most welcome Albie, and thank you very much!

Jean

Like the post above I want to thank you for going places, clamoring and scaling heights, and exposing hidden treasures I can not seek. I relish the time I sit reading your exploits, while smiling and sometimes downright grinning at your antics and play with words. It sounds like adventures I plan (usually in great preparation) and yet when I go forth, still manage to add some unexpected, not always welcome complexity. You are my kindred sister in heart and I knew it from the time I had the great pleasure of meeting you on your turf. May you and your family have a safe and healthy new year. And blessing the same to Moira Goodman.

Jo Woolf

That’s so lovely Jean! I think I should give Colin most of the credit as he was the intrepid one and I was struggling behind and trusting to his judgement! It was good fun all the same and this was such a beautiful place to visit. What you say about adventures reminds me of a quote by Roald Amundsen: “Adventure is just bad planning!” He was one of those explorers who planned all his expeditions down to the minutest detail because he didn’t want anything unexpected to happen. Yet most of the early women explorers were true adventurers at heart. Isobel Wylie Hutchison (in 1934) said: “The things you expected to happen! Could anything be duller?” So perhaps we should embrace the unexpected and trust that everything will be OK! Anyway, thank you so much and my very best wishes back to you and your family, for a happy and healthy new year.

Ashley

Jo, what an amazing post! A really good read! Thank you for sharing this wonderful story. Wishing you a happy healthy and wonder-filled new year.?

Jo Woolf

Thank you so much, Ashley! I really enjoyed visiting Kilneuair, which I’ve been wanting to do ever since I heard about it. Sometimes a place stays in your mind for a long time and I think this is one of those! Very best wishes back to you for the new year of promise, health and happiness.

Mary Smith

A fascinating post – and fabulous pics as always.

Jo Woolf

Thank you very much, Mary! I’m really glad you enjoyed it. The lighting was wonderful for photography. Doesn’t last long in winter but if you’re in the right place it’s perfect!

Bob Hay

Well Jo, you’ve certainly put Kilneuair on a lot of folks’ bucket list now. What a productive visit you both had. Colin’s photos captured the whole atmosphere brilliantly. On my visit the bracken was alive and well and I wished at the time I’d gone into Millett’s and bought a machete.

When I look at the almost organic wooden buttressing that’s been done (with the best of intentions no doubt) there are times I wish the authorities would just let old ruins collapse with a bit of dignity.

Notably at Castle Sween where obviously Jimmy the local brickie’s apprentice had been employed to throw up a brick support on one corner of a wall. Absolutely not even the faintest attempt to match the colours.

I’m sure many readers like myself would like to see your articles made into a book someday.

Jo Woolf

Thank you, Bob! I think we could have done with a machete too. I imagine I’d still be fighting my way through it if we’d gone there in summer. I agree with your point about the buttressing but I guess it’s all done with the best of intentions, and conservation approaches change so much over time. At least with courses of bricks there is no doubt at all what is the original structure! On the other hand there is something so clinical and spiritless about sites that have been cleaned up, ‘restored’ and made safe for visitors. I hope there will always be places like Kilneuair. That is an interesting thought about a book and I will ponder it.

Finola

What an amazing site and worth all the mildly colourful language and slidey wellies to get there. I love the idea of it being off the beaten track and of multiple periods like so many of our monuments here. Folklore assigns them to the 6th century, the architecture has elements of Romanesque but is mostly gothic, and there are Victorian intrusions all over the place – we can read it all if we look carefully. I just read a quote from an Irish historian that said, essentially, that history is written by a narrow range of people, but the landscape is also an archive, there for us to read sensitively to reveal its ‘cumulative diary’. Thanks fir a wonderful example of exactly that.

Jo Woolf

Thank you, Finola – it was all worth it! Yes, from reading your blog I can see many parallels in the ‘life stories’ of similar places in Ireland. I love the idea of the landscape being an archive, with a cumulative diary. How very true, in so many ways – geological, geographical, historical, spiritual. And with human stories, history is so selective about the names it preserves. With places like Kilneuair, part of me is glad that all we can do is try to glimpse what we shall never see – I love the feeling that these places have, and at heart I love how nature is re-absorbing them.

freespiral2016

What a wonderful rich site to discover and explore, so many hidden treasures. I feel there has t be a well there somewhere too!

Jo Woolf

Yes, we really loved exploring it! Interesting to wonder where the well might be – there are burns flowing either side, but that’s not unusual in itself as there are many on that hillside.

Robert Turner

Thank you so much for this story Jo. Loved it.

Jo Woolf

You’re most welcome, Robert, we loved exploring around Kilneuair that day! Glad to hear you enjoyed it.

Dalveen Pass

I visited here in the early 1990s before the walling collapsed and the buttressing appeared. The Oratory was in fine condition too. I took lots of photos (with a camera using film!). They came out very well as it was a bright and sunny day. The invasive vegetation looked like it was attended to by human hands. The “clawmarks” were visible on the wall. Remarkable place which looks to have deteriorated rather quickly in the last 30 years.

Jo Woolf

I would love to have seen it then! It sounds as if it has deteriorated quite quickly, as you say. The oratory is crumbling, and there are young trees growing from the stonework of both the oratory and the chapel. I wonder who (if anyone) is now responsible for its upkeep.