Blackness Castle

There are some castles that look best in the light of winter, with a muted sea and a fine drizzle descending from a sky of battleship grey. Blackness Castle, on the south coast of the Firth of Forth, is never going to look mellow, even in bright sunshine: it’s a glowering brute of a place, huge and forbidding. The occupants might have gone, but you can still feel their power.

On a cold January day we drove along the sea-front and crunched over the gravel in the car park. The castle loomed straight ahead, surrounded by lawns; we popped first into the small ticket office and visitor centre, which is housed in one of the more recent military-style buildings. There’s a lot of military style about Blackness.

We walked around the outside first, gazing up at the acres of uncompromising stone, punctuated by tiny windows. The guide book says that the ‘vulnerable’ south wall was given crenellations, from which assailants could fire upon approaching enemies. If people were attacking the castle from this angle, I can only admire their courage. The biggest feature at ground level is an arched cavity, beside which is a sign saying that this former entrance was walled up in the reign of Mary Queen of Scots. Obviously the doorway was too much of a risk.

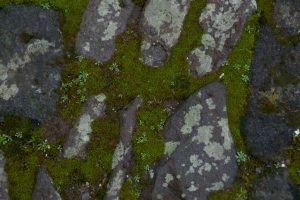

On the other side there’s a proper entrance, or more descriptively a tunnel, because that’s what it feels like. Passing through about 18 feet of curtain wall, you emerge into the courtyard and for a split second you want to turn around and go back. Beneath your feet is the bedrock upon which the castle was built – black and jagged, slippery with algae and rain. The Central Tower rises to the left, while the entrance to the South Tower gapes darkly to the right. You’re encircled by walls. The feeling is quite oppressive.

It has been speculated that some kind of fortress may have stood on this natural spur of rock in the Wars of Independence during the 14th century, but no traces of this remain. The origins of the surviving structure can be traced back to Sir George Crichton, who built a castle here in the 15th century.

Crichton was Admiral of Scotland, a wealthy landowner with estates in Midlothian. He came from an ambitious family who used the rivalry between James II and the powerful Douglases to their own advantage. George’s cousin, William, arranged the ‘Black Dinner‘ at Edinburgh Castle, when the 6th Earl of Douglas was murdered in the young king’s presence. James rewarded his allies but his greed for power meant that, in his old age, George Crichton was compelled to name the king as heir to his property. George’s son, also called James, wasn’t giving in so easily, and in 1454 he seized Blackness Castle with his father effectively a prisoner inside. James II, who loved guns more than just about anything, saw this as an irresistible challenge. He brought artillery, soldiers, and he even brought his own queen, Mary of Guelders, as a spectator. The bombardment must have been terrifying. Within a couple of weeks, Blackness Castle was his.

The Central Tower

Crichton inhabited Blackness Castle for a comparatively short space of time. The tower house – now called the Central Tower – was his residence. It originally had three floors, and a further storey was added around 1530. The original stairway is inside the wall, but an external stair tower was erected in 1667. As you wander from floor to floor, you realise that any lingering homeliness has long been overwritten, for one very good reason: for most of its existence, it has been a prison.

When James II acquired Blackness he appointed a royal ‘keeper’ or warden, charged with making sure that the castle was kept ready for a royal visit – which happened only occasionally. The keeper’s main duty was to take charge of an increasing number of inmates, most of whom – to begin with at least – seem to have been from the higher ranks of society. For these more noble offenders, the rooms within the Central Tower were converted into a relatively spacious and comfortable abode; their rooms were locked at night, but they were allowed to wander outside the walls by day.

Inmates of Blackness included Cardinal Beaton, Archbishop of St Andrews; Andrew Melville, Provost of New College, St Andrews; and Gilbert Kennedy, Earl of Cassillis.

The time of greatest change to the structure of Blackness was between 1537 and 1543, when, under the instructions of James V, Sir James Hamilton of Finnart supervised a transformation that massively increased its defences. The king had every right to be apprehensive. 1543 saw the beginning of the ‘Rough Wooing’, a war between England and Scotland, driven by Henry VIII’s wish to marry the infant Mary Queen of Scots to his own son. The reputation of Blackness as an impregnable fortress reached the ambitious English king, who instructed that, should Mary be captured by his forces, she should be taken to Blackness for safety.

Blackness seemed invincible, and doubtless it would have remained so, had it not been for the willpower of one man: Oliver Cromwell. With the execution of Charles I, Cromwell had gained power in England, but north of the border, where Royalist sympathies were strong, he still had battles to fight. Blackness was one of the fortresses holding out for Charles II, who had been crowned King of Scots at Scone in January 1651. Two months later, Cromwell’s forces bombarded the castle until the garrison inside it surrendered. The damage was repaired after the restoration of Charles II to the British throne in 1660.

The South Tower

The South Tower may once have contained kitchens and store-rooms during Crichton’s ownership. During the improvements carried out by James V in the 16th century, it was doubled in height and an impressive Great Hall was created on the second floor. This is about the only room that has any kind of welcome in it: the massive iron chandeliers give a hint of what it might have looked like when it was crowded with guests. You can imagine the colourful wall hangings, the tables piled with food, the rich gowns and jewels, the bustling servants, the boisterous conversation.

Because its layout bears a striking resemblance to a boat, with its curtain walls forming the curved hull, Blackness has been called ‘the ship that never sailed’. At its ‘prow’ is the North or ‘Stem’ Tower. This may have started off as a store-room but was later converted to a gun-battery, with a guardroom below and a miserable prison beneath, at sea level. The cells were washed out twice a day by the incoming tide.

Blackness ceased to be used as a prison in the early 1700s but a small garrison remained there throughout the Napoleonic wars, and even until the mid-1800s when invasion by France seemed likely. This explains the presence of the comparatively modern barracks and officers’ quarters in the grounds. Quite fittingly, the castle’s last use, before it passed into state care, was as an ammunition depot. Like a brave warrior, it was armed to the very last.

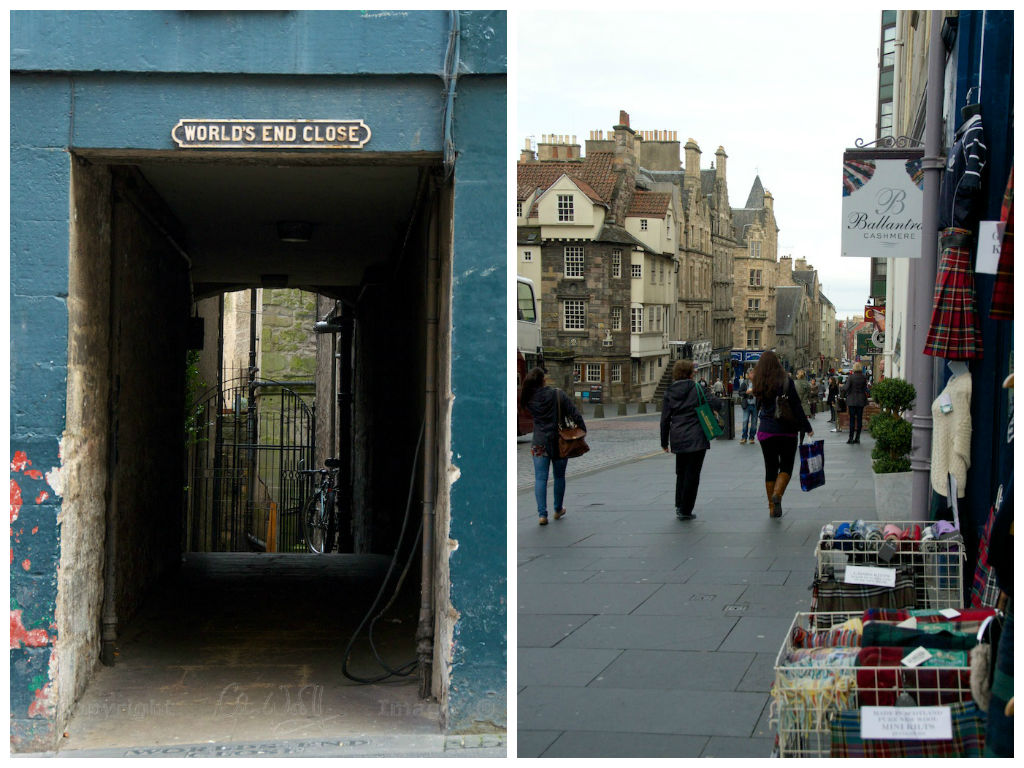

The views from the top of the towers, sweeping up and down the Firth of Forth, are impressive to say the least. Refreshing if you were escaping the heat of a banqueting hall; not so enjoyable if you were stationed there on guard duty in the teeth of a winter gale. With our hair suitably windswept, we took ourselves back down the stone stairs and out of the castle grounds, walking a short distance along the sea front and then climbing the low hill at the back. The ruins of an old dovecot stand here, and close by is the site of an early chapel, dedicated to St Ninian. The foundations are all that’s left: an information sign explains that, when Cromwell’s forces were deciding where to place their gun batteries, the chapel was inconveniently in the way, so it was demolished.

Remains of dovecot (above) and chapel (below)

Remains of dovecot (above) and chapel (below)

We pondered this for a while and then followed the path back down the hill. Colin, who went first, made a rather uncomplimentary remark about Cromwell and his contribution to historical sites, and immediately felt his arm being tugged quite firmly from behind. He turned because he thought it was me, and was surprised to see me still half-way up the slope. There was nothing more, and we weren’t faced with the spectre of an indignant army-general, so it remains a mystery.

In recent years, Blackness Castle has sprung to fame as a film location for ‘Outlander’, based on the books by Diana Gabaldon. The courtyard was used as a substitute for the Fort William barracks, and there could not be a more fitting location for the infamous flogging scene. There’s something about the atmosphere of Blackness; the history is vibrant and fascinating, of course, but there’s a hollow feeling, as if the walls remember things that you’d much rather not tune in to. Every castle has its dungeons, and most have seen conflict, but Blackness was devoted to war.

- Historic Environment Scotland and Blackness Castle guide book

- RCAHMS Canmore

- Undiscovered Scotland

- BCW Project: Cromwell in Scotland

Blackness Castle was a film location for the popular TV series ‘Outlander’. OutlandishScotland.com provide information on many Outlander sites and have published a PDF with accessibility information on Blackness Castle.

The castle was also used as a filming location for the movie ‘Mary Queen of Scots’ (released January 2019) starring Saoirse Ronan.

Images copyright © Colin & Jo Woolf

16 Comments

montucky

What a long and fascinating history that castle has! Your descriptions set my imagination running fast!

Jo Woolf

It has certainly witnessed a lot of history! Much of it I wouldn’t have wanted to see, but I’d love to have seen the royal visits and banquets. Glad you enjoyed it!

McFadzean

That must be the most appropriately-named castle in the world, Jo. It sounds like something out of a Robert Louis Stevenson novel.

Alen

Jo Woolf

That’s so true, Alen! Haha, that reminds me, there’s a village in Shropshire called Great Ness.

joturner57

Fascinating history, well-told, as usual Jo… Certainly an aptly named edifice… as noted in previous comments. Great photos.. you really captured a sense of its intransigent, obstinate occupants and owners. Strange anecdote about the sleeve-tug…must have sent the hairs up a little on both of your necks… btw hope all is well with you, and that you’re enjoying the summer..

Jo Woolf

Thank you very much, Jo. It’s a very photogenic place, just for its sheer physical presence. Interesting how all castles have their own unique atmosphere. We are well thank you, and hope that you are too! 🙂

dancingbeastie

What an evocative description of a grim auld place. I was almost shivering by the end. I quite agree with Colin about Cromwell, by the way, indignant ghosts or no!

Jo Woolf

Thank you! I was surprised by the intensity of it, really – unrelieved grimness! Yes, Colin is holding fast to his opinion about Cromwell, regardless! 🙂

TalesOfAScottishLassie

Need to go visit some of these places.

Jo Woolf

I hope you get a chance to do so!

Lorna

I love the ghost story about Colin, that’s spooky. I’ve never been inside Blackness Castle, but my dad and I walked round it earlier this year (or, more accurately, were blown round it in a freezing gale) and I thought it was a forbidding looking place. I didn’t know it had been used as a prison, perhaps that goes some way to explaining its sinister aura. The idea of the tide washing out the cells makes me feel a bit ill. It reminds me of a novel in which there’s a castle on an island with a dungeon that has the tide washing in like that. You wouldn’t want to be in the dungeon at high tide. Blackness sounds like the kind of place that would leave a strong impression on you afterwards, but not necessarily an altogether positive one.

Jo Woolf

It is pretty sinister, you’re absolutely right, Lorna. That’s the overall impression I had of it. No wonder it’s been chosen for filming locations – it has the atmosphere! Yes, Colin was quite convinced that someone had tugged him, and he doesn’t usually imagine stuff like that!

bitaboutbritain

Loved your description – it gave a real feel for the place. The prison cleaning regime was quite innovative – and I suppose it saved slopping out. And a potential ghost too – what more could you ask?! However, I’m inclined to wonder where we’d have been without dear old cuddly Cromwell 🙂

Jo Woolf

Thank you, glad you enjoyed it. Haha, yes, a castle with all the trimmings! Cromwell did so much, that it’s hard to consider what it might have been like without him! And what we might have left, more importantly. I would like to ask him what he thought he was doing with the Crown Jewels. 🙂

Brenee Carvell

Very nice walk through! I love castles and history, and we’ve toured several but missed this one- so difficult to hit them all, but we plan a trip back one day. Definitely could feel it’s formidable presence through your words. Thank you!

Jo Woolf

Most welcome, Brenee, glad you enjoyed it! Thank you for your nice comment. Blackness is certainly worth a visit – very memorable. I hope you get the chance to visit it.