The Govan Stones

On the south bank of the River Clyde in Glasgow is a district called Govan. Shipbuilding was once a major industry here, and now it’s a busy urban area of houses, flats, businesses and shops. Not the most obvious place to start looking for early medieval history.

But appearances can be deceptive.

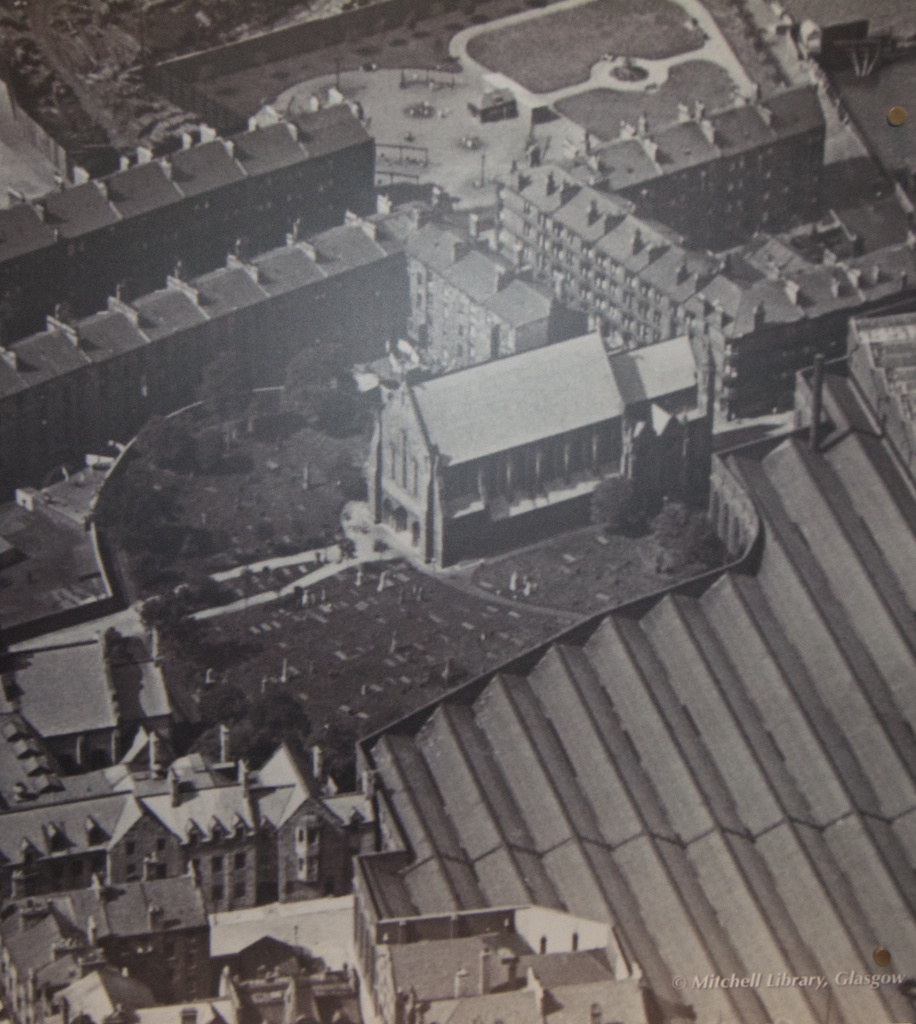

Secreted within this concrete jungle is a little time-bubble in the shape of Govan Old Parish Church. The building itself isn’t really that old – it dates from 1888 – but it’s surrounded by a much older graveyard; and if you step inside, you’ll come face to face with some jaw-dropping medieval treasures.

Secreted within this concrete jungle is a little time-bubble in the shape of Govan Old Parish Church. The building itself isn’t really that old – it dates from 1888 – but it’s surrounded by a much older graveyard; and if you step inside, you’ll come face to face with some jaw-dropping medieval treasures.

“One of the best collections of early medieval sculpture anywhere in the British Isles.” Gareth Williams, curator of the British Museum Viking exhibition

I’m not talking just about the fabulously carved Jordanhill Cross or the Sun Stone with its writhing bouquet of serpents, although in any other place they’d be the centre of attention. Lurking darkly in one of the transepts are the strangest sculptures I’ve ever had the fortune to see. They have such a presence that part of me wouldn’t even be surprised to hear that they got up and prowled around at night.

When you stand next to one of Govan’s enormous ‘hogback’ stones and run your hand over its scale-like surface, a horde of unanswered questions assail your mind like an invading army. What on earth do they represent? Who were they made for? What was their purpose?

They might be a thousand years old, but there’s nothing half-hearted about these extraordinary sculptures. Looking almost like prehistoric animals, they are solid, massive, dark and brooding. But before I can tell you any more about the hogback stones, I had better explain what on earth they are doing in Govan, in the heart of Glasgow. And it all comes back to the ancient but little-known kingdom of Strathclyde.

GOVAN AS A CENTRE OF POWER

When we think of early Scottish people, we tend to think either of the Picts or the Gaels, who later became known as Scots. The Vikings added a third ingredient to the melting pot of cultures. But there was a fourth, in the shape of the Britons of Strathclyde, who occupied a wide territory across southern Scotland and shared a common ancestry with the ‘Cymry’ or ‘Cumbri’ of northern England and Wales. Until 870 AD the ancient heart of their kingdom was ‘Alt Clut’, a fortress on Dumbarton Rock in the Firth of Clyde; but after a decisive defeat at the hands of the Vikings they moved their royal seat of power upriver, to Govan. There was a safe crossing here, close to where the River Kelvin joined the Clyde.

Sadly, little archaeological evidence is left to us. A fortified mound known as Doomster Hill is shown on some early maps, but this was obliterated by 19th century development. The name ‘Doomster’ suggests the ceremony and rituals of early medieval kingship, where laws were passed and judgements handed out, and the site may well have had prehistoric origins. Likewise, no trace remains of a possible royal residence on the opposite bank of the river, at Partick. All we have is the graveyard at Govan – and these remarkable stones.

The language of Govan

At the time when the Govan stones were carved, the people here would have spoken a northern Brittonic language related to Old Welsh. One theory is that the name comes from a Cumbric equivalent of ‘go’ meaning ‘little’ and ‘ban’ meaning ‘hill’. The ‘little hill’ may refer to the low mound of Doomster Hill.

So when was the first church built at Govan? According to legend, the Christian missionary St Constantine came here around 500 AD and chose to build a church next to a sacred well. His church would have been a modest wooden structure and no trace of it remains, but burials dating from the fifth or sixth century have been found in the graveyard, and the curving shape of the boundary hints at an ancient past. The discovery of a finely carved sarcophagus, obviously intended to hold some very important relics, brings us tantalisingly close to the truth. Did this ever hold the bones of St Constantine? It would be wonderful to know.

The Govan Sarcophagus

Unearthed in the graveyard in 1855, the Govan sarcophagus is carved with a huntsman on horseback and a number of animals that look like deer. It is richly embellished with beautiful interlaced knot-work.

THE HOGBACK STONES

“Archaeological evidence for early Christian burials… suggests continuity of an elite presence through the second half of the first millennium AD.” Tim Clarkson, ‘Strathclyde and the Anglo-Saxons in the Viking Age’

For the kings of Strathclyde, Govan was a royal burial ground, and it’s quite likely that the hogback stones marked their graves. Historians see a distinct Norse influence in their design, as they occur only where there has been a Viking presence – but strangely, there are no surviving examples in the Viking homelands of Scandinavia. Various interpretations have been placed on their appearance, but the most popular opinion is that they represent the tiled roof of a house that has been placed over the dead for protection.

It’s not that simple, however. The hogback stones at Govan have a central spine that seems quite animal-like – hence their name – and a couple of them are clasped at one or both ends by a carved beast that could be a bear or a serpent. They are asymmetrical, and to me their profile is reminiscent of a ship, with a prow and a stern.

The hogback stones at Govan were carved sometime between 900 and 1100 AD. Centuries of industrial pollution have blackened them, and when they were first made they would have looked quite different. For a start, it’s quite likely that they were painted – but how, and in what colours, we can only imagine. What we can say with more certainty is that they were intended to express the wealth, the power, and the importance of the people whose graves they marked.

The hogback stones at Govan were carved sometime between 900 and 1100 AD. Centuries of industrial pollution have blackened them, and when they were first made they would have looked quite different. For a start, it’s quite likely that they were painted – but how, and in what colours, we can only imagine. What we can say with more certainty is that they were intended to express the wealth, the power, and the importance of the people whose graves they marked.

What makes the hogback stones so strange?

Until now, all the medieval grave stones that I’ve seen have been long, rectangular and relatively flat, often carved with swords and low-relief effigies and the symbols of a person’s trade. They convey an impression of pride, but also of someone having surrendered his soul to another realm and wishing to be remembered with respect and love. There’s an openness and a feeling of trust.

Not so with the hogback stones at Govan. Built to withstand the wrath of giants, they look as if their whole purpose is to keep something in! You get a sense of someone being locked within the earth, safe from all kinds of unspeakable evil. Far from trusting their dead to the tender care of angels, these people heaved a huge lump of sandstone over the grave and added some sinister-looking beasts for extra security. The warning is clear: mess with me at your peril.

There are more hogback stones dotted around Scotland and Northern England, but the five at Govan represent the country’s largest collection. They are also the biggest and heaviest examples yet to be found.

GOVAN’S OTHER STONES

Govan has such a rich heritage of carving that it has given rise to the term ‘Govan School’ to describe the craftsmanship in this particular area. Three magnificent stones that stand just within the entrance of the church were designed to portray the beliefs and values of the Strathclyde Britons.

The Sun Stone

One of Govan’s earliest carvings, the Sun Stone has a large central boss from which four serpents are emerging. This is thought to represent the Christian concept of redemption and resurrection, and it is a symbol that is found elsewhere in Scotland and Ireland. On the other side is a decorated cross and a mounted warrior with a spear and possibly a sword; his hair appears to be tied in a ponytail. Was he a king of Strathclyde?

The Cuddy Stane

The top part of the ‘Cuddy Stane‘ is missing, but a drawing survives from 1856 which shows a horserider carrying a long weapon and mounted on an animal that looks more like an ass than a horse – hence the stone’s name, ‘cuddy’, which is Scots for ‘donkey’. This has led to speculation that it may represent Christ’s entry into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday.

The top part of the ‘Cuddy Stane‘ is missing, but a drawing survives from 1856 which shows a horserider carrying a long weapon and mounted on an animal that looks more like an ass than a horse – hence the stone’s name, ‘cuddy’, which is Scots for ‘donkey’. This has led to speculation that it may represent Christ’s entry into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday.

The Jordanhill Cross

This stone gets its name from the place where it was found – the garden of Jordanhill House just across the river, where it had been taken in relatively recent times. It is carved with another mounted warrior amid some superb knotwork, almost as if the stonemason was challenged to showcase his skill.

To historians, the shaping of the slab at the top suggests that it was designed to fit into another stone, possibly a cross-head. At the entrance to the churchyard stands a modern replica of the Jordanhill Cross, showing how it may have looked when complete.

Early medieval grave slabs

A surprising number of early grave slabs are dotted around the church, having been brought indoors for protection. Between the 17th and 19th centuries some of these stones were re-used for contemporary burials and were inscribed with initials. It is only recently that their historical significance has been put into context and fully understood.

A surprising number of early grave slabs are dotted around the church, having been brought indoors for protection. Between the 17th and 19th centuries some of these stones were re-used for contemporary burials and were inscribed with initials. It is only recently that their historical significance has been put into context and fully understood.

Until the late 1900s these cross-carved slabs, along with the hogback stones, lay outside the church and were fully exposed to the elements. Unfortunately, that is not all they were exposed to: the demolition of the adjacent Harland and Wolff shipyard in 1973 sent rubble tumbling over the wall, and at least 16 of the recumbent stones were lost, while several more were damaged. Historians are painstakingly trying to recover details about the missing stones, using evidence such as old black-and-white photos.

What happened to the Britons of Strathclyde?

Around 1050, the kingdom of Strathclyde was conquered by the increasingly powerful Scots. King David I founded a new diocese in Glasgow in 1114, and the old church at Govan was gradually abandoned. As for the Britons themselves: “They were no longer Cumbri but had become ‘Scots’ like their new political masters. Inevitably, as time wore on, the deeds of their forefathers began to fade from memory. Soon only the sculptured stones remained, a handful of monuments scattered across the land, to bear mute witness to a forgotten people.” (Tim Clarkson)

VISITING THE GOVAN STONES

If you haven’t already been to Govan, I recommend that you do so because there’s nothing like seeing these amazing stones at first hand. Over the last few years the Govan Stones Project has undertaken a major new re-display scheme which shows off the stones within the church to their best advantage, accompanied by useful interpretation boards.

Govan Old Parish Church is open to visitors from 1st April to 31st October 2015, between 1 and 4 pm. Admission is free, although donations are welcomed. There’s lots more information on the Govan Stones website, including a map showing how to get there.

A service takes place in the church every weekday morning. “The Old Church at Govan remains active, making it one of the most long-lived centres of Christianity in Britain.”

Sources:

- The Govan Stones

- Heart of the Kingdom

- ‘Strathclyde and the Anglo-Saxons in the Viking Age’ by Tim Clarkson

- Senchus – Early Medieval Scotland

- The Govan Stones – BBC feature

- Govan and Linthouse Parish Church

Photos copyright © Colin & Jo Woolf

Further reading…

If you enjoyed this, you might like to take a look at the magnificent Dupplin Cross which stands in St Serf’s Church at Dunning in Perthshire.

51 Comments

Rachael Hale aka 'The History Magpie'

Thanks for an amazing post, Jo. I loved the hogback stones and carvings, they look so tactile I just wanted to run my hands along them. Once again you’ve added to my dream destination list.

Jo Woolf

I’m glad to hear it, Rachael! They are worth coming to see. The hogbacks really are tactile, as you say, and I’m sure former generations must have thought so too. I would love to have seen what they looked like originally. This is what I love most about history!

housesandbooks

What a great essay! I wish I was in Scotland and could go see these stones myself. The hogback stones look vaguely menacing….but they also resemble huge ears of half-shucked maize. Very strange. I’ve never heard about them before and was fascinated. Many thanks for this post!

Jo Woolf

Thank you! I wish you could see them too, but I’m glad to have brought you a virtual tour. The hogback stones do have a definite air about them, like sleeping creatures that you don’t want to disturb. I love your idea about the maize!

I wish you could see them too, but I’m glad to have brought you a virtual tour. The hogback stones do have a definite air about them, like sleeping creatures that you don’t want to disturb. I love your idea about the maize!

Susan Abernethy

Oh Jo! It is so fabulous you got to visit the stones. I don’t know that I’ll ever get there so I’m glad to see your pictures and read your history. Fantastic!

Jo Woolf

I know, Susan, aren’t they amazing? I’m very glad I finally got to see them. I have learned so much about Govan and Strathclyde over the last year or so. Wouldn’t it be wonderful to have seen the royal palace and Doomster Hill, as well? There’s a real magic about this era, possibly because it’s so shadowy.

http://vivinfrance.wordpress.com

An incredibly interesting and surprising post. Jock was born less than 18 miles from Govan, and had driven through it many times, but had never seen these fabulous stones. Thank you for all the hard work you put into sharing these stories and pictures with us.

Jo Woolf

So glad you enjoyed it, Viv, and I didn’t know that Jock was from around there. I don’t know Glasgow very well but I knew I had to go and see these amazing stones (Colin did the navigating, mind you!)

Anny

I remember an old episode of Time Team which was featured a dig at Govan, but I don’t remember any of the fabulous details you’ve covered here – this is fascinating stuff and it really makes me want to go and have a look myself.

Jo Woolf

I shall look that up, Anny – I remember reading about it somewhere. There are some old drawings of Doomster Hill – how frustrating to know that it existed until only about 100 years ago! The stones are displayed really well, and are certainly worth going to see if you’re ever in Glasgow.

david

Shame on the demolition firm responsible for the Harland and Wolff shipyard!

Jo Woolf

Aaaghh, I know, David! But in those days, even though it seems so recent, people didn’t know how important these things were. Loads of lovely old places were pulled down in the 60s and 70s – I know that from living near Shrewsbury, and lots of black-and-white buildings were lost.

Pat

My first thought when I saw the hogbacks was ‘armadillo’. That was quickly followed by ‘not in Scotland’. They’ve really piqued my curiosity. What ever they are, I like the idea they were placed on graves to protect those within. Great article! Thanks for all your hard work.

Jo Woolf

I love the idea of armadillos! They do look like that, you’re right. The hogbacks really do capture your imagination, because there seem to be so many elements to them. Thank you, Pat!

They do look like that, you’re right. The hogbacks really do capture your imagination, because there seem to be so many elements to them. Thank you, Pat!

winderjssc

Absolutely fascinating.

Jo Woolf

Thank you, Jessica! The whole story of Strathclyde is really fascinating.

Caroline

Another super post, Jo – I am fascinated by the hogback stones; they have a definite “presence” about them. And what a wonderful collection of old crosses and grave slabs. I love how such a treasure trove of history has survived in an area that’s changed so much over the years.

Jo Woolf

Thank you, Caroline! Govan has a superb collection of stones, and it is good that so many of them have survived in the churchyard, as you say. The sarcophagus was unearthed while digging graves, apparently.

blosslyn

Amazing, they really do look as though they might just wake up and wander off. I think I have seen some, for some reason I keep thinking of of Luss on Loch Lomond, in the churchyard there, but they were smaller, but very similar. Great to learn all about them, will have to visit one day and have a look

Jo Woolf

You’re right, Lynne, there is one at Luss: http://canmore.rcahms.gov.uk/en/site/42529/digital_images/luss+st+kessog+s+church+and+churchyard/

I haven’t seen it myself, but from the pics it looks to have a slightly different kind of decoration. There are some early cross-slabs there too. I didn’t know there was an old church at Luss – another one for the list!

I hope you get to visit Govan sometime, you’d love it!

blosslyn

Oh good,, I wasn’t sure, I will have to pop in next time we pass and take some photos, still working on Steve for later on in the year. I went to Govan many years ago when it was a shipyard, Steve designed cooking ranges to go on ships, so I used to go with him sometimes. Never went in the church though, so that will have to go on the list as well…….this never ending list which grows daily haha

Jane

Fascinating write up! This is all new to me. Great pictures and research. Thanks for sharing!

Jo Woolf

Thank you, Jane! I only heard about them myself fairly recently, but they are stunning when you see them up close.

justbod

Another great article Jo with lots of interesting details! I particularly loved your own observations on the hogback stones. They always remind me of some kind of large pods, waiting to split open and hatch…I will definitely have to make time to visit – your writing and the photography is very inspirational!

Jo Woolf

Thank you very much, Justbod! That’s very kind of you. Yes, they do look like pods, you’re right – they have a very organic look about them! I hope you get to see these stones sometime because they are just extraordinary.

mariegm1210

Another fascinating post Jo with so much detailed history. My knowledge of this period is shadowy but I’ve learned so much from you! Plus fabulous photos!!

Jo Woolf

Thank you very much, Marie, and for sharing it! I had no idea about the Kingdom of Strathclyde until a year or so ago, but I find it absolutely fascinating. There’s so much we don’t know!

mariegm1210

Reblogged this on Marie Macpherson and commented:

Fascinating history of the Govan Stones, Glasgow

phil

did you all know that there was a castle here in IBROX, just where the tower flats used to be many years ago

Jo Woolf

I didn’t know that, Phil. Do you have any more information? I know of Crookston Castle, not far away.

Janice Parkinson

I dread to say I used to play on them in the fifties using the hogs as horses and stones as little shoppes ,did not know the importance of them but we had lots of fun

Jo Woolf

That’s amazing, Janice! I think any kid would be fascinated by them! You probably weren’t the first, by many generations!

You probably weren’t the first, by many generations!

christinelaennec

A fantastic article, Jo. I was at the morning service at Govan Old today, and at coffee we were joined by a small conference of archaeologists and carved-stone experts taking place there. One of them told me that a big problem in Scotland is that, with the Church of Scotland closing and selling off so many of their churches due to declining numbers, there isn’t always any provision made for looking after the carved stones in the churchyards. I hadn’t thought of that. Another topic of discussion was work done in Sweden on analysing the chisel marks in carved stones in order to identify individual carvers. Amazing! Govan Old is a lovely church and there is a morning service there every weekday morning.

Jo Woolf

Thank you, Christine! I didn’t know that Govan Old was your ‘local’ church. I’ll add a bit into the article about the services. That’s a very good point about churches being sold off and carved stones being neglected – I hadn’t thought of that either. Identifying stone masons from their marks sounds like a science in itself!

christinelaennec

I go there once a month with a friend who plays the organ. I wrote a post about the morning services there, if you want to link: http://christinelaennec.co.uk/2014/05/16/morning-service-at-govan-old-church-glasgow/ I also wrote a post about the stones, but it’s nowhere near as thorough and informative as yours, so I will put a link to this post in it. I thought you would like the chisel-mark research!

Jo Woolf

Thank you again! Love the link and your photos. Nice to hear from someone who goes there regularly! It’s such a good thing that the church is still in use, as you say.

James Logan

Hi Jo this must be one of the best kept secrets in Scotland,as someone who was born and brought up in Govan fifty years ago I had no idea that these treasures were in Govan, as I now stay only 20 miles away I will be making a point to visit soon. Thanks and keep up all your good work.

JL

Jo Woolf

Hi James, I’m really pleased you’ve discovered them in that case! You’re not the only one who hasn’t heard of them but I don’t think they have had much publicity up to now. I really hope you get to see the stones, as they are fabulous! Bless you for your kind comments.

tearoomdelights

Truly remarkable. The hogback stones look like something out of Doctor Who, only friendlier. They seem very appealing and I would like to see them for myself. I’ve never been to Govan but I always associate it with Rab C Nesbitt – a far cry from these architectural wonders.

Jo Woolf

You’re right, Lorna – they almost look like some kind of alien being! It’s certainly worth going to have a look, and we found that you can park just in the entrance to the graveyard. I had only a vague idea where Govan was, until we went there!

Candia

Have been desperate to see these for a couple of years now. Trouble is, my visits up north are so infrequent and usually tied to some family business.

I have an association with Govan as my ancestor was William Dixon, Ironmaster of Govan.

Thanks for sharing the photos!

Jo Woolf

They are well worth the trip, Candia. Such a presence when you see them at first hand. That’s a very interesting association that you have with Govan!

djwinchell

I received an entirely different impression of the hogback stones. They reminded me of the ancient barrows where the most important person were buried in the middle and the mound built up over them. The barrows were built to impress and protect. The hogback stones certainly do that.

Jo Woolf

That’s a very interesting comparison, and I do agree with you. It’s quite likely that they had the same intention. They are amazing, aren’t they?!

james barclay

Hello jo, TK’u for your sharing unbelieveable knowledge, is Excitingly Brilliant,I wonder about a story,Re: Long Stem Clay Pipe,embed’n’Slate, told me about It’s use,by my G/pa,a miner who”d worked in “Slate Hills,of Stepps”if a ,possible connection of which Doomster Hiils in the Map..!

Jo Woolf

Hi James, Thanks for your kind comment. I’m not sure I fully understand the connection with your Grandpa’s clay pipe and Doomster Hill – do you mean he worked there? It sounds like a wonderful heirloom!

Kirsty

Can anyone tell me what type of stone was used to make the Hogback stones please? Been hunting for ages on the internet but can’t find anything. Thanks

Jo Woolf

Hi Kirsty, that’s a good question! One person who could probably tell you is Tim Clarkson who writes a blog at https://earlymedievalgovan.wordpress.com/ – meanwhile if I come across anything myself, I’ll let you know!

Jo Woolf

PS. This article from the BBC seems to suggest they are sandstone http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-18172678

Irene McKay

I really enjoyed visiting these stones this summer and found your article very informative about them. Great work, Irene

Jo Woolf

Thank you very much, Irene! Really glad you enjoyed your visit. I think the Govan stones are amazing – what a history and what a presence they have!